We all see things that are not there, every now and again.

Particularly things that are on our mind. For example, if you're thinking about someone, you're increasingly likely to see, or think to have seen, that someone out on the street. This is because our perception is biased by our expectations. Put differently, we try to fit what we see into mental templates.

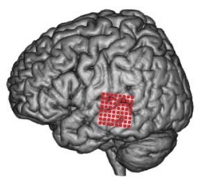

A recent study by Smith and colleagues shows this in a new way, which I think is kind of cool. In this study, participants watched patches of completely random noise, like static on television. But the participants were tricked. (Yes, they keep falling for it.) They were told that on half of the trials a face was hidden in the noise. And they were instructed to indicate on every trial whether they had seen a face or not.

The analysis that Smith and colleagues performed was quite simple. They took the average of the patches of noise on which the participants indicated that they had seen a face, and subtracted from this the average of the non-face patches. If the participants had just been randomly pressing keys, this procedure would have led to a uniformly black image. After all, the average of lots of noisy patches is uniformly grey. And grey minus grey is black.

But this is not what happened! Out of the noise emerged clear (well, let's say reasonably clear) outlines of faces. Apparently, the participants tried to match their template of what a …

Editors will try to boost their journals' impact factor, of course. This is good, for the most part, because it provides editors with an incentive to create a decent journal that publishes good science. But as Wilhite and Fong show in a recent edition of Science, there's a dark side as well: Coercive self-citation.

Editors will try to boost their journals' impact factor, of course. This is good, for the most part, because it provides editors with an incentive to create a decent journal that publishes good science. But as Wilhite and Fong show in a recent edition of Science, there's a dark side as well: Coercive self-citation.

![A cover of one of Elsevier's corporate sponsored [url=http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australasian_Journal_of_Bone_%26_Joint_Medicine]fake scientific journals[/url].](/images/stories/blog/misc/australasian_journal.jpg) Elsevier is one of the largest academic publishers, and is notorious for charging extremely high prices. This places a considerable financial burden on publicly funded academic institutions, who are, for various reasons, practically forced to buy Elsevier content. Elsevier has also engaged in other dubious practices, such as actively supporting

Elsevier is one of the largest academic publishers, and is notorious for charging extremely high prices. This places a considerable financial burden on publicly funded academic institutions, who are, for various reasons, practically forced to buy Elsevier content. Elsevier has also engaged in other dubious practices, such as actively supporting