The Great Bowerbird is a curious bird. The males spend most of their time building bowers, which are elaborate structures, constructed solely for attracting females. These loveshacks are decorated with stones (and sticks, bones, etc.) in a very specific way: Small stones are put near the entrance of the bower; Larger stones are put further away. When looking out from the inside of the bower, which is were the females stand during courtship, this arrangement leads to a striking distortion of perspective. You can see this in the image below (compare b to c). In a sense, the size gradient of the stones flattens the image, reducing the subjective perception of depth.

Photos from Kelley & Endler (2012) and Anderson (2012)

The male bowerbird is quite picky about this arrangement. If the size gradient is disturbed (by a biologist, for example), the males immediately restore it. But why? Since the purpose of the bower is to seduce females, it is tempting to speculate that the distorted perspective is aesthetically pleasing to female bowerbirds. Who, as mentioned above, tend to stand inside the bower as they watch the male perform his dance of seduction.

But there could be numerous other explanations. For example, the males could simply be too lazy to carry big stones all the way to the bower. Or something like that.

But no, it appears that the distorted perspective really is what matters. In a recent issue of Science, Kelley and Endler investigated what the perfect size gradient is …

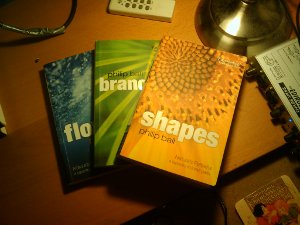

The diversity of the issues that Philip Ball takes on in his trilogy on nature's patterns is overwhelming. Most of them cannot even be said to have much in common: Jupiter's red spot cannot be explained in the same way as the shape of a honeycomb cell. Yet, despite his eclectic subject matter, Philip Ball manages to tell a coherent story. One that goes far beyond stamp collecting of interesting factoids.

The diversity of the issues that Philip Ball takes on in his trilogy on nature's patterns is overwhelming. Most of them cannot even be said to have much in common: Jupiter's red spot cannot be explained in the same way as the shape of a honeycomb cell. Yet, despite his eclectic subject matter, Philip Ball manages to tell a coherent story. One that goes far beyond stamp collecting of interesting factoids. Well... I don't know, and perhaps it is just a matter of style without any real reason. Fashion, in a sense. But it does strike me that this is a relatively new phenomenon, and that scientists in the past were much more equivocal in their writing. The quite recent past, even. Take, for example, Michael Posner, who wrote in the abstract of his seminal 1980 paper Orienting of Attention that '(...) the possibility is explored that (...)'. Or Giacomo Rizzolatti, of mirror neuron fame, who wrote back in 1987 that '(...) the hypothesis is proposed that postulates (...)'. Both of these sentences (which were of course cherry-picked for the occasion) convey a modest degree of belief in ones own theory and/ or findings: I believe in X, but I could be wrong.

Well... I don't know, and perhaps it is just a matter of style without any real reason. Fashion, in a sense. But it does strike me that this is a relatively new phenomenon, and that scientists in the past were much more equivocal in their writing. The quite recent past, even. Take, for example, Michael Posner, who wrote in the abstract of his seminal 1980 paper Orienting of Attention that '(...) the possibility is explored that (...)'. Or Giacomo Rizzolatti, of mirror neuron fame, who wrote back in 1987 that '(...) the hypothesis is proposed that postulates (...)'. Both of these sentences (which were of course cherry-picked for the occasion) convey a modest degree of belief in ones own theory and/ or findings: I believe in X, but I could be wrong.