Suchow and Alvarez report a very compelling optical illusion in an upcoming edition of Current Biology. The illusion is very simple and I was quite surprised that it actually works. A cloud of colored dots is arranged in a circle around a central fixation point. In one condition, the dots gradually change color, but they don't move. As you would expect, it is very easy to spot the color changes in this condition. However, in another condition, the dots move around as well as change color. Surprisingly, in this condition the color changes are extremely difficult to detect! This is demonstrated quite nicely in the video below (provided by the authors).

How does the illusion work? An important clue is that retinal motion is required. If you match the movement of the dots with your eyes, thus eliminating the retinal motion, it becomes considerably easier to detect the color changes (not as easy as when the dots are static, but this is presumably because it is difficult to match the movement perfectly). Simply put, this suggests that we detect the color changes with neurons that “see” only a small part of our retina. If the dots move around on our retina, they are continuously “seen” by different neurons, and this compromises our ability to detect changes.

References

Suchow, J. W., & Alvarez, G. A. (2011). Motion silences awareness of visual change. Current Biology, 21, 1–5. [PDF]

The experiment was as follows. In a training phase, bees learned that they could get a sugar-reward by flying to a small square in the center of a larger square. Sometimes the small square was blue and the surrounding square was yellow and sometimes it was the other way around. To learn this task, the bees had to use both spatial (center square vs surrounding square) and color cues (since the squares were defined by color). In the test phase, they found that the bees had successfully learned to solve this “puzzle”.

The experiment was as follows. In a training phase, bees learned that they could get a sugar-reward by flying to a small square in the center of a larger square. Sometimes the small square was blue and the surrounding square was yellow and sometimes it was the other way around. To learn this task, the bees had to use both spatial (center square vs surrounding square) and color cues (since the squares were defined by color). In the test phase, they found that the bees had successfully learned to solve this “puzzle”. Initially, I wanted to buy an e-reader with a small display, which are considerably cheaper than the large ones, and just scroll through the pdfs like you would on a regular computer. Luckily I didn't, because e-readers are way to sluggish to comfortably scroll through a document. This is because e-ink displays have a very low refresh rate (i.e., it takes quite some time for the image to change). Most e-readers have the option to reformat (reflow) text, which means that the reader tries to increase the font size while maintaining a reasonable layout. For books, which tend to have a fairly straightforward layout, this works fine, but for multicolumn .pdfs (i.e., most academic papers) the results are disastrous. So basically, if you want to read academic papers, you will want an e-reader with a sizable display. The IRex has an 8 inch display, which is just large enough …

Initially, I wanted to buy an e-reader with a small display, which are considerably cheaper than the large ones, and just scroll through the pdfs like you would on a regular computer. Luckily I didn't, because e-readers are way to sluggish to comfortably scroll through a document. This is because e-ink displays have a very low refresh rate (i.e., it takes quite some time for the image to change). Most e-readers have the option to reformat (reflow) text, which means that the reader tries to increase the font size while maintaining a reasonable layout. For books, which tend to have a fairly straightforward layout, this works fine, but for multicolumn .pdfs (i.e., most academic papers) the results are disastrous. So basically, if you want to read academic papers, you will want an e-reader with a sizable display. The IRex has an 8 inch display, which is just large enough …

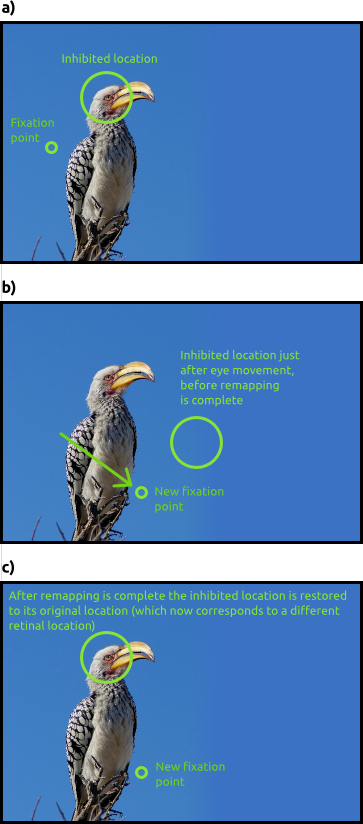

The “problem” that I'm referring to is that with every eye movement, the retinal image of the world changes enormously. Therefore, if we were to take changes in the retinal image as evidence for changes in the world around us, we would perceive a dizzyingly unstable world. Which, clearly, we don't. We may be vaguely aware of the fact that we make eye movements, but subjectively it does not feel as though eye movements interfere with our sense of “visual stability”. Apparently, the visual system somehow compensates very effectively for eye movements.

The “problem” that I'm referring to is that with every eye movement, the retinal image of the world changes enormously. Therefore, if we were to take changes in the retinal image as evidence for changes in the world around us, we would perceive a dizzyingly unstable world. Which, clearly, we don't. We may be vaguely aware of the fact that we make eye movements, but subjectively it does not feel as though eye movements interfere with our sense of “visual stability”. Apparently, the visual system somehow compensates very effectively for eye movements.